What did we miss?

Morgan Wade Talks 'Reckless' Album, Sobriety - Rolling Stone

“I just got it in my head that I could form a band,” Wade recalls. “It would either piss him off or get him back, either one.” She found her future players online — ”the safest thing for a 19-year-old female to do,” she says dryly — and went through with her plan, not only winning over her ex but forming a group known as the Stepbrothers in the process. Naturally, her boyfriend joined.

While the ragtag Craigslist band eventually dissolved, Wade, now 26, evolved into a committed musician and touring artist. Her debut solo album Reckless , which arrived in March, carries the ragged edge of a singer-songwriter who’s been putting her nose to the grindstone for some time. In a voice like worn leather, Wade describes desperate, spontaneous relationships that feel the strongest when they’re at their breaking point. “Lay me down on the floor in the kitchen/Show my angry heart what I’ve been missing,” she sings on the chorus to the soft-rock anthem “Take Me Away.”

It’s not the first trajectory or sound you might imagine for an artist born and raised in Floyd, one of the historic birthplaces of country music in the United States and still a mecca for bluegrass fans the world over. Wade recalls spending Friday nights as a child at the Floyd Country Store, sitting on her grandfather’s lap as fiddlers, guitarists, and folk singers entertained a crowd of dancing locals and tourists alike. That certainly became a part of her, but she didn’t want traditional hoedown country to be where her own music began and ended.

“I have a country accent, so everyone assumes that I’ll just sing country music, but I like to do a lot more than that,” she says. “I just want to play whatever I want to play, and right now, that happens to be more like rock music or pop music.”

Sadler Vaden , longtime guitarist for Jason Isbell & the 400 Unit and Wade’s producer on Reckless , along with Paul Ebersold, recalls meeting Wade at a festival in Floyd and later watching one of her performance videos. He was struck by how little she shared with the sound of Nashville, Texas, or the Appalachians. “I just immediately was drawn to her voice,” Vaden says. “Something about it reminded me of Melissa Etheridge or something, right out the gate.”

Vaden called up Wade, and shortly thereafter, the two were crafting an album together in a Nashville studio, in what Vaden describes as a “really chill” process. He considers Tom Petty’s 1988 album Full Moon Fever (the one that opens with “Free Fallin’”) to be the “template” for Reckless , and that’s certainly felt in its production style, which oscillates between country-rock circa 2004 and Don Henley-esque pop-rock. But it hardly stays within those boundaries: “Northern Air” is an atmospheric folk song built around acoustic strings and drum brushes, while the snaptrack and earworm hook on “Last Cigarette” would be right at home with mainstream country’s biggest streaming hits.

“A lot of people wanted to corner Morgan as, ‘You’re the next Tyler Childers,’” says Vaden. “And she did not want to be that. I’ll even say that, at first, I maybe thought that she was that too. But she loves pop music. And so I just tried to help her achieve the sound that she was hearing in her head.”

While Wade has been writing songs for as long as she can remember, it wasn’t until she started performing with the Stepbrothers at 19 that she truly became comfortable onstage. Overall, it was a fruitful time for her work. The Stepbrothers played shows in her college town of Roanoke and the surrounding area, and for the first time Wade got the sense that more people besides herself were interested in the songs she could write. Still, the stress and odd hours of touring weighed heavily; she developed a drinking problem, compounded by the constant after-show beers and bar runs.

“It’s difficult sometimes, when you’re ready to go onstage and you wouldn’t mind a little liquid courage,” she says. “You got a lot of downtime after you set up a new soundcheck, everyone’s sitting around, and there’s a lot of cool bars [in town] and stuff like that.”

Best Motown Songs: Supremes, Gaye, Stevie Wonder, Smokey Robinson - Rolling Stone

In 1959, an aspiring songwriter and record producer named Berry Gordy Jr. borrowed $800 to start his own record label in Detroit. Good investment. Within a year, Motown had its first million-selling record, with the Miracles’ “Shop Around.” By 1969, the label would place dozens of records in the Billboard Top 10 as it reshaped the sound of pop music for a generation, thanks to its somewhat contradictory mix of assembly-line consistency and individual artistic brilliance, integrationist upward mobility and black self-assertion, fierce competition and familial camaraderie. “I was so happy whenever I got a hit record on one of the artists,” said Smokey Robinson , the label’s greatest songwriting genius. “Because they were my brothers and sisters.”

Opinion | Why Grammy Winners Might Never Sound the Same Again - The New York Times

Since the 1960s, pop music has been ruled mostly by what's known in the business — and to your ears — as the verse-chorus form: The verse sets the scene, the pre-chorus builds tension, and the chorus reaches a climax. Then, the cycle starts again: verse, pre-chorus, chorus. It's the fun, if slightly predictable, roller coaster we've been riding for decades.

For a simple yet powerful and classic example, think back to "(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman" sung by Aretha Franklin. She starts out, "Looking out on the morning rain," thinking of how she "used to feel so uninspired," then brightens up talking about her new love, singing, "You're the key to my peace of mind." The instruments — horns, strings, drums — brighten up right alongside her and peak, cathartically, with the titular line everyone knows and loves (backed by a literal chorus).

Listeners loved this new form so much that it was soon the industry default. The music theorist Jay Summach has found that by the end of the 1960s, 42 percent of hit songs used verse-chorus form. By the end of the 1980s, that figure had doubled to 84 percent.

But things quickly began to shift in the 2010s. A mix of generational churn, creativity spawned by the digitization of music production and the dilution of the industry's top-down structure — paired with the fragmentation of the media and adaptations to the streaming economy — has warped song structures. Beyond radio play, songs are five-second memes, 12-second TikTok soundtracks, 30-second ads and two-and-a-half-minute club anthems.

Listen to the Top 40 charts of the last decade and a surprising trend emerges. The form of pop as we know it seems to be changing before our ears. Take Billie Eilish's " Bad Guy ," one of the biggest hits of 2019. It displays few of the values we typically associate with pop: the peaking decibel levels, the soaring melodies, the recurring phrases that are easy to sing along with, all wrapped into a steadily repeating climax that neatly tucks itself in between verses.

Instead, the chorus of "Bad Guy" offers the listener a low-key, half-whispered, stream-of-consciousness rhyme scheme ("Just can't get enough guy / Chest always so puffed guy /I'm that bad type / Make your mama sad type") over muffled drums and bass.

The musical high point of the song comes afterward instead in the form of a wordless, ear-grabbing synthesized melody. In a telling bit about the role bottom-up self-production plays in this trend, the nebulous sound that brought Ms. Eilish, born in 2001, to prominence was not forged in a high-end corporate studio but in her brother Finneas's bedroom. Last year, she won the Grammy for Best New Artist and "Bad Guy" won Song of the Year.

Turn the radio dial (or hit "shuffle" on Spotify or Apple Music) and you'll invariably find songs with intentionally broken choruses, like Bad Bunny's " Si Veo a Tu Mamá ," which unleashes hook after blistering hook on top of a " Girl From Ipanema " interpolation, creating a cascade of catchy sections without a central chorus.

(The success of Bad Bunny — the most-streamed artist of 2020 — is a testament to not only pop music's changing forms but also its widening cultural borders .)

In case you are keeping track:

How Cruz is Bridging the Gap Between Electronic and Latin Pop Music - EDM.com - The Latest

"At the early age of four, I had an ear for music and by five years old, I learned how to play the violin," Cruz told EDM.com . "I then realized I wanted to make music that would resonate worldwide."

The road to contemporary crossover linchpin was an unconventional one for the New York-based DJ and producer. While studying audio engineering in his early years in the industry, Cruz, who plays numerous instruments, began making music for a TV channel and found himself performing on weekends with a Top 40 cover band. However, the small venues and weddings at which he appeared were a far cry from the lavish NYC nightclubs he can be seen performing at today, such as LAVO, PHD, and Soho.

He eventually landed a gig as a tracking and mixing engineer in a recording studio in Venezuela, where he had the opportunity to compose a song for legendary Latin pop artist Paulina Rubio . The track, "Me Gustas Tanto," appeared on Rubio's 10th studio album Brava! and topped Billboard's Latin Pop Songs chart, leading to a BMI Award win for Cruz.

Enter "My Baby Shot Me Down," Cruz's latest genre-bending masterwork that serves as a tour de force after years of workhorse-like growth. Considering the bright future of the crossover space, Cruz sees the new single as a launchpad to merge the worlds of Latin pop and electronic dance music.

"['My Baby Shot Me Down'] is the first of many other crossover friendly songs that I will be releasing throughout 2021," explained Cruz, who finds inspiration in musical legends Queen , Michael Jackson , and The Beatles . "My formula is simple, I collaborate with amazing mainstream and electronic artists, songwriters, musicians and producers to maintain its essence while sprinkling our Latin flavor and colorful fusions."

Cruz, Adam Nazar, and V of Vossae joined forces for "My Baby Shot Me Down," a massive Latin pop and electronic crossover.

The work of Cruz's collaborators here is not to be understated. The additional production provided by Nazar, a Miami-based musician and electro DJ, is stellar through the song's arrangement. V of Vossae also provides a stentorian vocal performance, which has a powerful yet slow-burning presence as it slithers along to the hypnotic sound design of the track's producers. "How talented Adam and Victoria are, they have something unique that everyone needs to know about," Cruz gushed. "Its like a feeling that you can hear in this song that makes it that special."

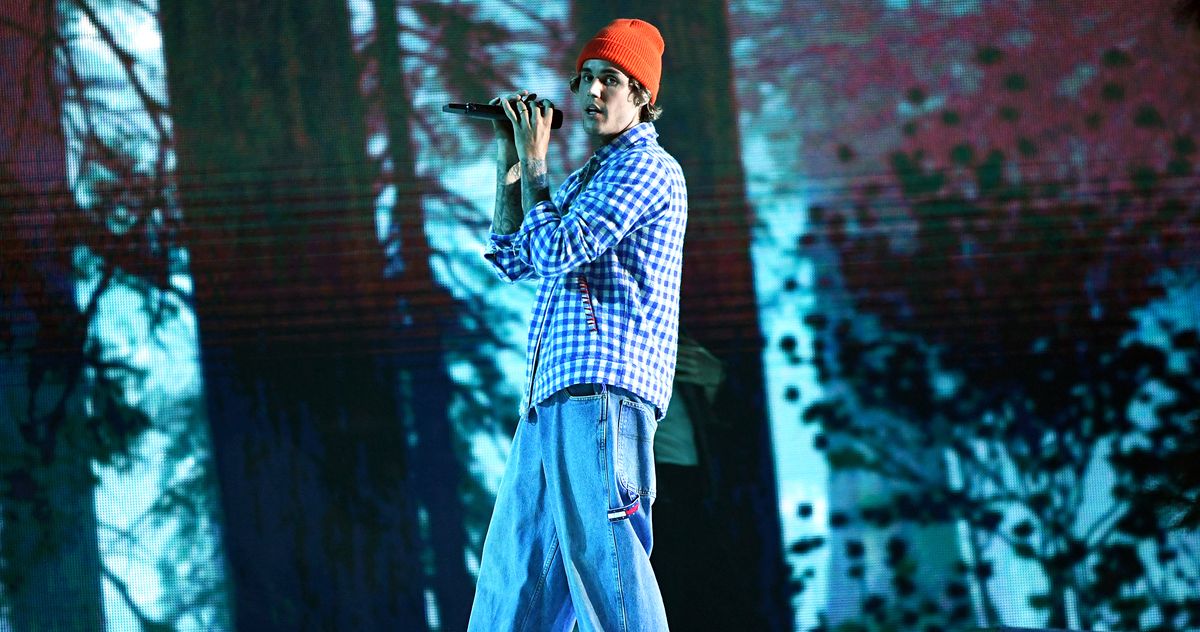

Justin Bieber's 'Justice' Songs Explained By Harv and Aldae

Bieber backed up his claim a month later when he released "Anyone," his most undeniable pop song in years. Now, with Justice out , the turn looks even sharper. Released just 13 months after Changes , the new album positions Bieber's R&B phase as more of a detour. Instead, Justice picks up after Purpose , which Vulture music critic Craig Jenkins recently hailed as "one of the previous decade's finest pop projects." But while much of Purpose diluted EDM trends into pop hits, Justice prefers the polished, synth-fueled pop-rock of the 1980s as a jumping-off point.

It's a lot to process from Bieber, who's given few interviews on the new music. So to look behind the scenes of Justice , Vulture spoke to two of Bieber's key collaborators on the album: Bieber's band member since 2010 and current music director, Bernard "Harv" Harvey, and songwriter Gregory "Aldae" Hein. Harv co-wrote and co-produced "Somebody" and "Peaches," while Aldae co-wrote "2 Much," "As I Am," "Unstable," and "Somebody." Both collaborators described the fast-paced, detail-oriented process behind Bieber's sonic pivot. "It's about making sure that this album is going to be the best album of the year," Harv says. "Every producer and writer, we all had that same idea."

With Justice released so close to Changes — Bieber debuted first single "Holy" just seven months after putting Changes out — it may have looked like the album was cut from the same sessions, like Taylor Swift's folklore sequel evermore . "The original plan was to do two albums back-to-back," Harv says, but to keep the processes separate. "We literally started from scratch," he adds. "We wanted Justice to have its own sound, its own identity, so we put those old songs back on the shelf." To better establish that divide between projects, Bieber brought a number of new writers on for Justice , including Aldae. "People know Justin as a pop star," he says of the shift. "I think he crushes the R&B, but I personally love this style of music more with him."

The argument over whether pop music is moving away from the album form persists, but Bieber has remained focused on it. The approach pays off on Justice; critics have praised its cohesion. (Even Pitchfork called it "Bieber's smoothest album-length statement to date.") "It's a format, how we track-list the album," Harv explains of the 16 songs. "We kind of let the album grow as you listen to it." And it does, with Bieber easing his way from slower ballads at the beginning of the album into more upbeat songs after the "MLK Interlude." " We literally sat down and listened to every song and made sure that they all sounded like they were on the same project," Harv adds. "For me, it was kind of hard, 'cause I had way more songs that were supposed to be on the album, but it just didn't [fit together with the sound]. That was a moment for me to be like, Okay, it's about the full body of work. " The sessions became less about sound than a unifying spirit of the work. As Aldae puts it, "There are songs you can dance to, but I think every song makes you feel something."

When Bieber teased a photo of him planning the track list on social media, an impressive list of featured artists — from Khalid and Daniel Caesar to Burna Boy and Beam — caught fans' eyes. On all the songs they worked on, Harv and Aldae said the features came from Bieber himself. With "Peaches," Bieber switched to A&R mode right after cutting his vocals. "Like two hours later, he FaceTimed me," Harv says. "Justin was like, 'Yo, like I think we got one.' I'm like, 'What do you mean?' He was like, 'I got Giveon on, on the feature.'" The up-and-coming R&B singer first cracked the top 40 as a feature on Drake's "Chicago Freestyle" last year. Then, about a month later, Harv got another call. "Just how Justin is, he'll FaceTime me out of nowhere," he says. "He was like, 'Hey, let's get Daniel Caesar on it.'" Some of the other features, though, came down to the wire. Aldae notes that both Khalid 's and rapper-singer the Kid Laroi's parts on their respective songs came in days before the album's release .

And yes, Bieber's feature choices also extended to Dr. King. "2 Much" opens with his famed quote, "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere." King's daughter, Bernice King, later said she approved the quote along with the album's longer interlude, while Bieber committed to work with the King Center among other social-justice organizations. Aldae admits he didn't plan on putting the quote in "2 Much." "At first I was a little confused when I saw MLK in the credits," he says. "A lot of classic albums have an insert at the beginning, something to bring you into the album. People close to me have told me there was a disconnect between those two things, but to me, it was just like, 'Yo, welcome to my album.' MLK, one of the greatest speakers of all time. Why not?"

While he introduced the world to the ideas behind Justice in a Twitter thread, Bieber had been thinking on them for months. In December, Bieber had a meeting with his collaborators about the meaning driving the project. "He talked about how important this album was to us, and how his name actually was translated to justice [from Latin], and how important it was for him to make an impact, and how he was in this high position. He was calling on us to help be the vessel for what he wanted to channel into the world," Aldae says. "He was very vulnerable with us about wanting to put that goodness into the songs."

Parp stars: the 15 best saxophone solos in pop music

In certain quarters, the sax has picked up a reputation for '80s cheese – but these naysayers don't know what they're missing

Capable of far more than a slightly sleazy solo (though to be honest that’s part of the appeal) the presence of this golden-hued instrument has elevated hundreds of songs into straight-up super hits. In the business for some woodwind? Look no further…

As a kid, David Bowie flicked through some old copies of Melody Maker , and came across the jazz saxophonist Ronnie Ross – who would later play on Lou Reed 's 'Walk on the Wild Side'. "I was like nine or 10 years old, and I phoned him up and said, "Hello, my name is David Jones, and my dad's helped me buy a new saxophone, and I need some lessons," Bowie recounted to Performing Songwriter . He successfully persuaded Ross, and Bowie later ended up playing sax on his own track 'Changes'. For his 1983 album 'Let's Dance', meanwhile, Bowie recruited a horn section, and opening track 'Modern Love' is powered by some of his entire catalogue's finest saxual healing.

In a tradition that possibly dates back to Bucharest-based Europop pioneer Alexandra Stan and her 2011 horn-playing tribute 'Mr Saxobeat', pop has made increasing use of the saxophone over the last decade. And for sheer feel-good factor, it doesn't get much better than the high drama Celtic-flavoured sax that powers Carly Rae Jepsen 's 'Run Away With Me' – a melody so ridiculously memorable that it became a Vine meme in which it was played by everyone from Dolly Parton to Ross Geller .

A colossal slab of wide-eyed rock'n'roll, Bruce Springsteen 's commercial breakthrough 'Born To Run' is an operatic epic to chasing "a runaway American Dream" – each vivid scene more saturated than the last. "I want to know if love is real / Oh, can you show me?" Springsteen sings. Clarence Clemons steps into answer with an enormous sax solo giddy on joy and excitement. Something of a legend in the medium, Clemons also lent his woodwind talents to…

On 'Born This Way', Lady Gaga brought together Eurotrash excess and shoddy attempts at speaking German (see: 'Scheiße') with straight-up rock ambition direct from the playbook of one of her favourite artists, Bruce Springsteen. In fact, when it came to injecting some sax factor into 'The Edge of Glory', Gaga rang up E Street Band member Clarence Clemons and asked him to fly to New York to record that very same day. He injects an effortless sense of fun that felt missing from other mainstream pop music at that time – and Lady Gaga dug back into '80s pop revival long before it was everywhere again.

A cover of Dolly Parton 's country-tinged original, Whitney Houston 's version of 'I Will Always Love You' – recorded for 1992 schmoozy movie The Bodyguard – amps up the ballad factor and makes belting use of Houston's powerhouse vocal. And just when you think things can't possibly get any more dramatic, in comes a yearning-filled sax solo from Kirk Whalum – who over the years has also lent his talents to Luther Vandross, Everything But The Girl , and Al Green .

Produced by David Bowie and Spiders With Mars member Mick Ronson, Lou Reed's twangy anthem for Andy Warhol's Factory superstars fades out with a honeyed sax solo, which could happily keep going into infinity. To create the famous rock'n'roll moment, Bowie booked his childhood saxophone teacher Ronnie Ross and turned up to surprise him at the session.

There's a fidgety, wonky undercurrent to ’80s Aussie rockers’ Men At Work's 'Who Can It Be Now' – and much of this comes down to the band's Greg Ham and his tenacious sax hook, which weaves its way through the entire new wave number. The parping solo itself was recorded in a single take. The inescapable main melody later cropped up on Jason Derulo 's mildly irritating cowbell fest 'Love Hangover'. So, OK, sax solos aren’t all good news.

The Case For Devo's Induction Into The Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s biggest snub was born just 40 minutes down the road in Akron.

Devo, nominated this year, deserves “rock’s highest honor.” Sure, the avant-garde new wave band had only one major hit, “Whip It.” But its influence, inspiring acts as diverse as Neil Young and Rage Against The Machine, makes up for its lack of commercial success.

“Their substance and artistic integrity was underappreciated in its time,” says David Giffels, former Akron Beacon Journal reporter and co-author of We Are Devo! Are We Not Men? We Are Devo! which is set for rerelease in the next year or so. “There was this very politically driven tension and anger behind what sounded like pop music.”

Long before MTV hit the airways, the band pioneered music video production with art-directed music films, launching Casale’s director career. Jim Mothersbaugh’s electronic drum and MIDI innovations became the backbeat of pop, while Mark Mothersbaugh would score the films of Wes Anderson and TV shows such as Rugrats.

“I think their role as innovators is what makes them so important today,” says Giffels.

Gimmick or one-hit wonder Devo is not. It’s time these local legends get into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. We talked to Giffels, who is currently revising his book on Devo with co-author Jade Dellinger, about the Akron band’s lasting legacy.

CM : How do you think coming from Akron influenced their sound?

DG: They’ve often talked about the fact that being from Akron led them to having all this industrial iconography to their look and to their, even to their sound. That’s because they were in an industrial town. If they had come up in Silicon Valley, they might have different elements of aesthetic and culture and maybe adapted them through the same intellect and imagination but with different pieces on the surface.

CM: What do people misunderstand about Devo?

DG: Devo was an art concept for years, starting in 1972, before they were really a band. They only became a viable rock band when Alan Myers joined in 1976 as the drummer. For me, the best musical version of Devo is as a really powerfully dynamic rock band.

CM: Are Devo a one-hit wonder?

DG: By the literal definition, they’re a one-hit wonder because they didn’t have any other true hits. “Whip It” was their only commercial success, and it peaked at No. 14 on the Billboard charts in 1980. And when they got that one hit was when they had, what could be seen as, the goofiest look of their career, which was the flowerpot hats or energy domes. So if those are the only two things that most mainstream rock fans know, it’s easy to dismiss them. It seems very superficial. So I think what people should know about Devo is the depth of their like sort of artistic backstory, and the fact that they created this whole sort of deeply thought and conceived theory of “de-evolution” long before they really manifested as a rock band.

No comments:

Post a Comment